This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Detours and fine dining: the history of the Michelin Guide

By Rory FH Smith | 21 December 2022 | Food & Drink

For 120 years, the Guide has been synonymous with the world’s best dining experiences. We look back at the surprising origins of the ultimate restaurant review

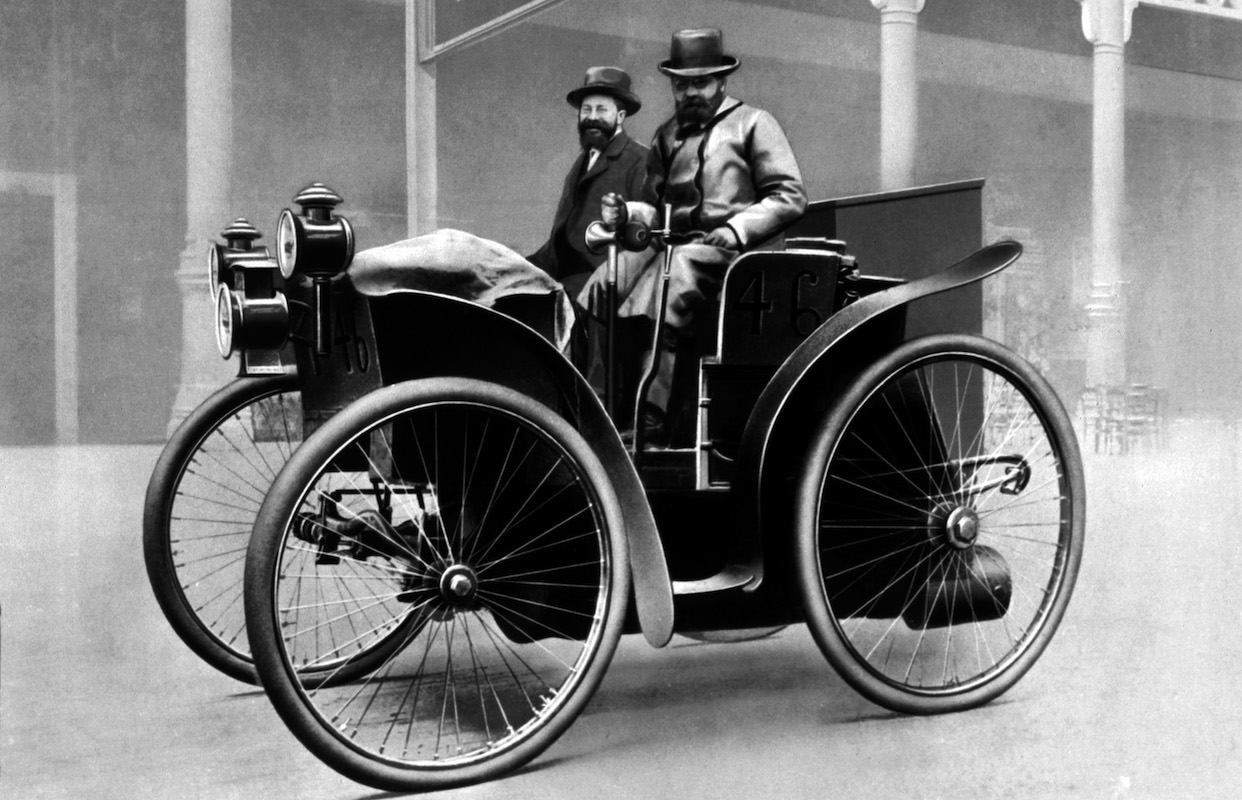

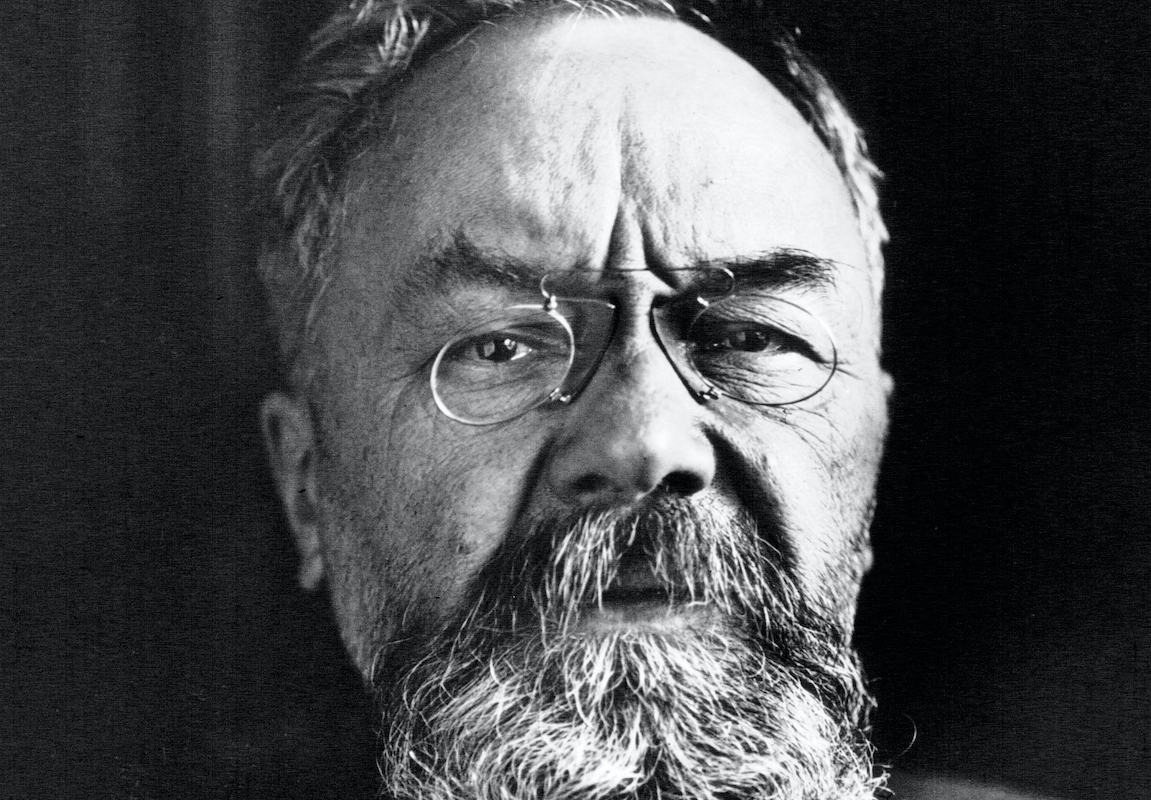

In 1900, brothers André and Édouard Michelin were scratching their heads trying to think up a solution to a familiar business problem. Their fledgling eponymous tyre company had been running for 11 years but their supply of potential customers was proving problematic. Raised in the quaint French town of Clermont-Ferrand, the brothers had taken over their grandfather’s ailing manufacturing business that made farm equipment and rubber balls in 1889, renaming it Michelin & Co.

Within two years, the pair had pivoted the business and pioneered the first detachable pneumatic bike tyre. By their seventh year, the brothers had graduated to car tyres, helped beat the world speed record and invented a charismatic cartoon character made from tyres called Bibendum – and soon known as ‘the Michelin Man’. By all accounts, their company was off to a good start, but André and Édouard had higher aspirations.

The problem they faced appeared to be out of their control. Despite the invention of the first French automobile in the late-1850s, cars were slow to take off. By 1900, there were no more than 3,000 cars in the country. Compared with the trusty horse and carriage, motorcars were noisy, dirty, slow, complicated and, above all, hugely expensive. But André and Édouard were undeterred.

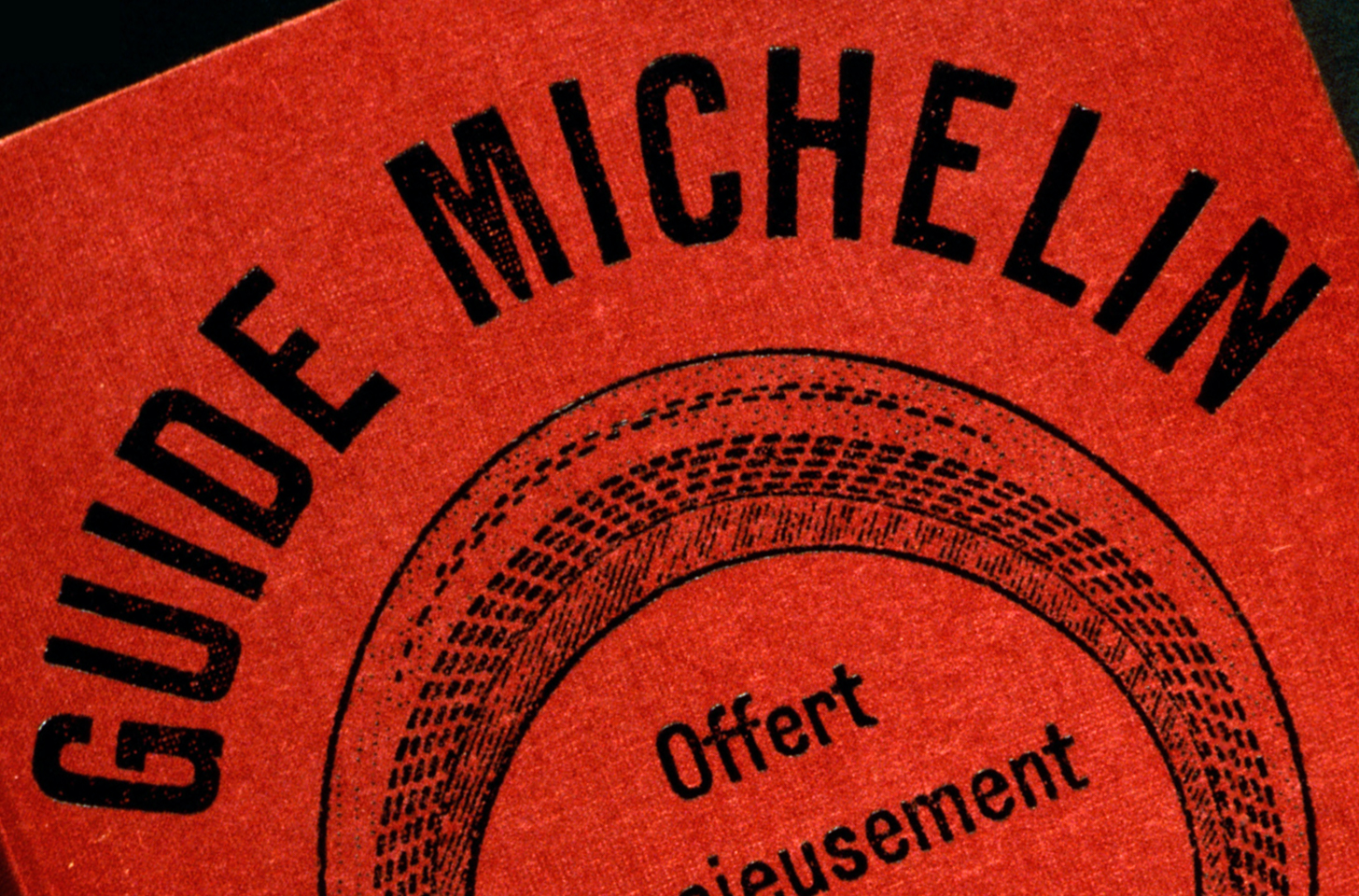

Fuelled by a grand vision for France’s automobile industry and André’s early career as a cartographer, the pair set about developing a guide book to help motorists develop their road trips. With this savvy marketing manoeuvre, it was hoped that the tyre manufacturer’s diversification into publishing would make car ownership more attractive and, in turn, create more demand for the tyres they ran on. The guide took the form of a small red book filled with useful information for travellers, such as maps, information on how to change a tyre, where to fill up with fuel, and – perhaps most importantly – where to find board and lodgings along the way.

In time, the brothers would be recognised as part of a wave of 20th-century French visionaries, joining the likes of engineering genius Gustave Eiffel, fashion designer Coco Chanel and aviation pioneer Louis Blériot. Together, they would transform France into an industrial powerhouse. Initially, André and Édouard produced the guide and distributed it free of charge to motorists, spreading the Michelin name far and wide within their small, but financially empowered, target audience. Road maps soon followed, making use of André’s skills as a cartographer, which resulted in a rich mix of publications that enticed drivers to explore and take detours to find the best dining spots in the country. With more motorists out and about touring the nation in their cars, the brothers knew an uptick in tyre sales would soon follow.

After two decades, the popular guide was still produced and distributed free of charge to motorists. There seldom seemed a reason to change the formula until, one fateful day, when André stopped at a tyre shop to see a stack of his beloved guides being used to prop up a workbench. Understandably disappointed, the brothers rethought their offer and launched a new guide priced at seven francs: they reportedly reasoned that “man only truly respects what he pays for.” Alongside the cover price, the guide also expanded into listing hotels in Paris as well as lists of restaurants according to specific categories. Now fully independent of advertisers and with a growing reputation, the guide could begin to flex its powers of advocacy and influence in hospitality as well as motoring.

By 1926, the Michelin brothers had gathered a team of mystery diners to visit and review restaurants anonymously, a secret process that remains closely guarded to this day. Awarding stars to only the finest dining establishments, the inspectors initially handed out only one star until a hierarchy of zero, one, two, and three stars was introduced five years later. One star was awarded to restaurants with “high quality cooking, worthy of a stop,” two signified an establishment with “excellent cooking, worthy of detour,” and three was reserved for places with “exceptional cuisine, worthy of a special journey.” To this day, the criteria and covert way of awarding the stars remain unchanged. As the Michelin Guide simply states, it’s a form of recognition “coveted by many chefs but bestowed upon only an excellent few.”

While the prominence and influence of the little red guide began to grow, so did the appearance and profile of the company’s inflated mascot, Bibendum. The brothers originally employed artist Marius Rossillon – better known as O’Galop – to create the charismatic cigar- smoking and monocle-wearing mascot (below), taking his name from the strapline, “Nunc est bibendum”, which means “now is the time to drink”. An odd choice of phrase for a motoring supplier, the slogan was later updated to “The Michelin Man drinks up obstacles,” often written alongside images of the character sipping a cocktail of broken glass and nails.

Despite the eccentric backstory, Bibendum was a hit with the wealthy, middle-class elite who liked to drive, drink and dine in equal measure. “The monocle, the cigar and the girth of Bibendum were all signifiers of the leisured bourgeois male, and the Michelin ranking system made Parisian/ metropolitan norms the standard for attribution of cultural value throughout France and around the world,” said Professor Patrick Young, a specialist in 19th- and 20th-century French history at the University of Massachusetts- Lowell in an interview with the BBC in the year of Bibendum’s 120th birthday.

Since the inception of André and Édoard’s cunning marketing initiative in 1900, more than 30 million copies of the guide have been sold worldwide. While the Michelin star system is a globally recognised measure of culinary success and achievement, it continues to rate and rank more than 30,000 establishments, across 30 territories and three continents.

But the guide’s reputation as a tastemaker doesn’t come without controversy. The institution’s ability to instil everything from triumph to terror and fear into the hearts of even the hardiest chefs is remarkable, particularly given its industrial origins. Celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay was reportedly reduced to tears when a restaurant under his name went from two stars to zero, while chefs such as Skye Gyngell have been known to reject the rating, citing the extreme pressure that comes with it. Even the neat description under the stars can be interpreted as a discreet warning of the potential outcome: “Getting a star (or three) can change the fate of a restaurant”.

Despite its controversial reputation, the guide and its infamous rating system now celebrate over 120 years in operation. While André and Édoard wouldn’t have predicted the scale of the guide’s success, as we emerge from a period of prolonged global restrictions, this unlikely institution – standing for exploration, excellence and enjoyment – has never felt so relevant and welcome. Vive le Guide Michelin.