This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

As 3D printing hits the worlds of art and fashion, can technology really replace Rembrandt?

By Henry Hopwood-Philips | 4 December 2017 | Culture

We explore the collaboration between two Dutch museums and technology giants that is rocking the art world

The post-war period has been dominated by the question of whether art and politics have stuck to their historical claims. While art has typically judged the culture from which it’s sprung and politics has stuck to more pedestrian matters, the two appear to have flipped in recent years, art is becoming increasingly sensitive to market demands, losing any pretence of belonging to a higher order.

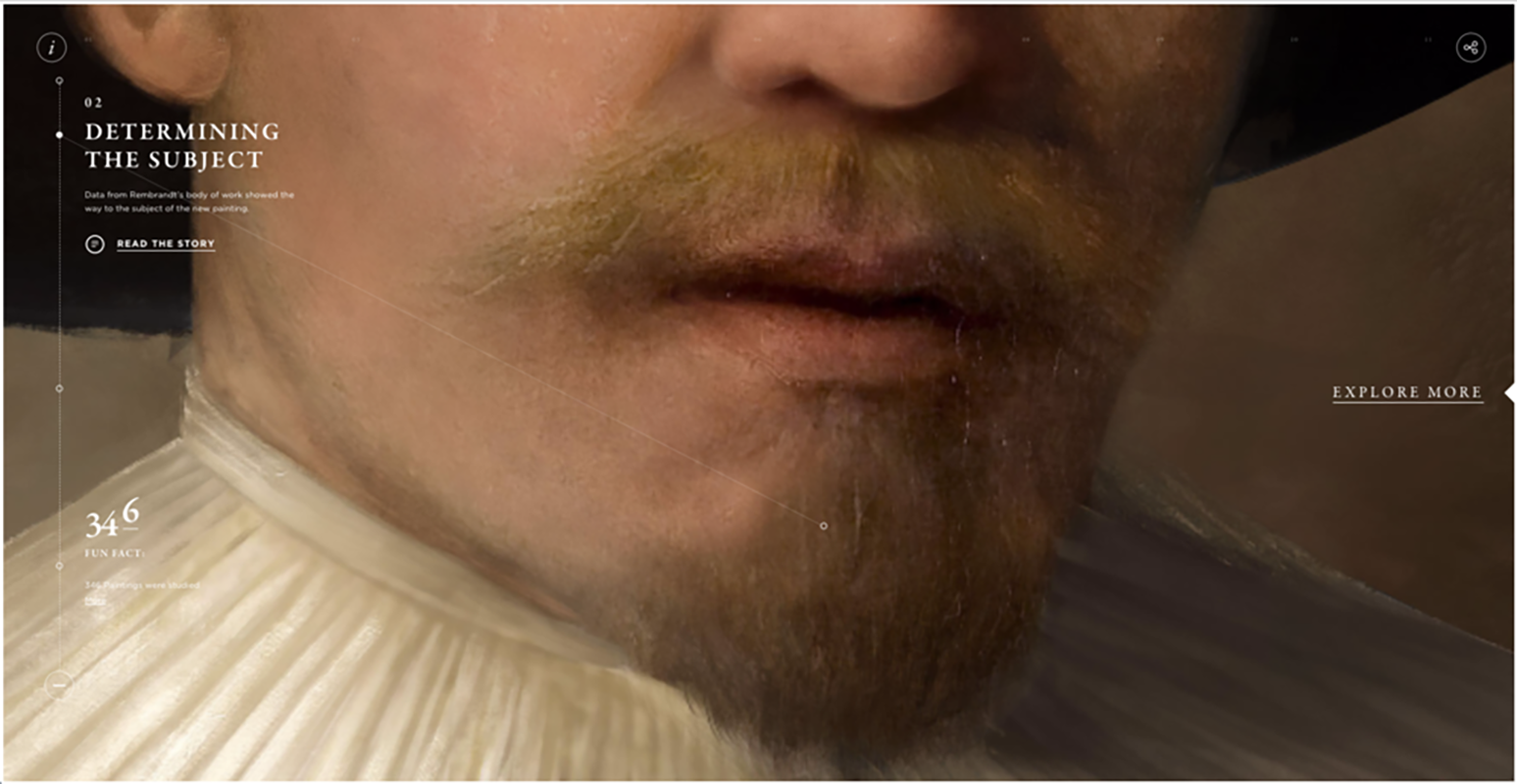

But a new framework is being born that may possess the power to overturn the conventional debate. Here, we look at how developments in the technological sphere may unleash the greatest dreams of artists, or reduce art to a province of the economy. The first shots across art’s bow came from a collaboration between two Dutch museums, Microsoft, ING and the Delft University of Technology. In 2016, they created a faithful replication of a Rembrandt painting by mining the data (i.e. the metrics) of all the artist’s previous works. A 3D printer was even employed to give the work an authentic brush-stroked texture.

If the work of a canonical painter like Rembrandt can be reproduced by changing variants in an algorithm, not only does that throw into question the worth of the current stock of Masters, but also the value of what one has historically considered “genius”. Adam Greenfield, author of Radical Technologies, suggests the project calls time on our traditional notions of creation.

“The essence of [the artist]”, he asserted, “is perceiving patterns and having stereotyped responses to those patterns that they can improvise on.” When AI can do this better than us, why still laud the creator? It’s a question that touches on whether art has progressed or perished as its relationship with the tools of production has become more enmeshed. >>

Related: Artist Ewan David Eason goes for gold with his new living exhibition at 45 Park Lane

Once art was about the human touch behind a paintbrush, chalk or pencil but now new tools require different skills. And this new repertoire appears to reinject a new animus into the ancient Greek debate on the merits of techne (practical knowledge) and episteme (abstract knowledge), with the former clearly gaining ground today.

Meanwhile, artists – while being required to master new tools – are also, on a deeper level, at risk of being overwhelmed and exhausted by the sheer amount of options offered. Myriad means of expression rarely result in empowerment. Instead, a surplus of tools or ideas tends to immobilise an artist. There’s a sinking feeling – in an infinite sea of content – that everything must have been done by someone else; hopes of originality are easily pilloried as juvenile or hubristic.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Technology also has the potential to improve transparency. Historically, the art world has suffered opacity when it comes to tracking the provenance and movement of items. This is almost entirely because it still relies on a paper-based system where corruption, theft, loss or destruction regularly blight the industry. But this may quickly become a thing of the past if Blockchain (the technology behind Bitcoin) is deployed.

Essentially a public database for global transactions, its genius lies in its lack of a central authority (which could potentially be corrupted). Instead, its ledger is distributed through a vast network of users, which keeps things tamper-proof and neutral. >>

Related: The Louvre art gallery prepares to put Abu Dhabi in the frame

Several start-ups are already seeing its value and adopting ways to implement it in the art world. Some of the biggest contenders include Verisart, which generates certificates of authenticity and verifies works in real-time. e company Ascribe, which pins unique cryptographic IDs that retrieve the entire histories of items. While Monegraph offers a similar service, too, but also promises to send alarm bells ringing if a person attempts to claim ownership of the same artwork.

Much of the value in these companies derives from the virtues of decentralisation. For too long, mediators have made transactions in the art world both expensive and clumsy. In the future, the hope is that contract systems will spring up that make the artist an equal and transparent partner with investors in ventures. ‘Smart Contracts’, which promise to self-execute the terms of agreements, ensuring that profits are divided fairly and without delay, will quickly follow.

And, finally, mechanisms like Weifund (which, unlike Kickstarter or Indiegogo turn supporters into investors instead of dumping them after reaching targets) will be likely to proliferate among artists, too. All these developments promise to place artists back at the centre of their own banquets, rather than begging for crumbs from others. They assure the market that legal wrangles will be settled in a world of a few clicks instead of months or years of court battles. They guarantee that automated code is more reliable and honest than the elites that currently govern the processes.

The real problem is, however, that though they may be correct, these are revolutions that affect the body rather than the spirit of art. Of course, governance, identity and supply chains matter, as do investment patterns and contracts. But arguing about the capillaries while ignoring the heart, could be seen as an exercise in futility.

This is why the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine Gallery, did not daydream about the future grammar of the economic system that art found itself in, when questioned about the nature of future art. Instead, he answered: “It is the famous ‘etonnez-moi’ of Diaghilev and Cocteau.” To have one’s artistic norms shattered, modified and astonished is not the same as the neo-liberal dream of complete financialisation. And to pretend so would be to make a mockery of art.