This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Artist Ewan David Eason goes for gold with his new living exhibition at 45 Park Lane

By Michelle Johnson | 20 October 2017 | Culture

The Mappa Mundi artist exclusively tells Tempus about the very personal secrets hidden in his collection and embracing technology

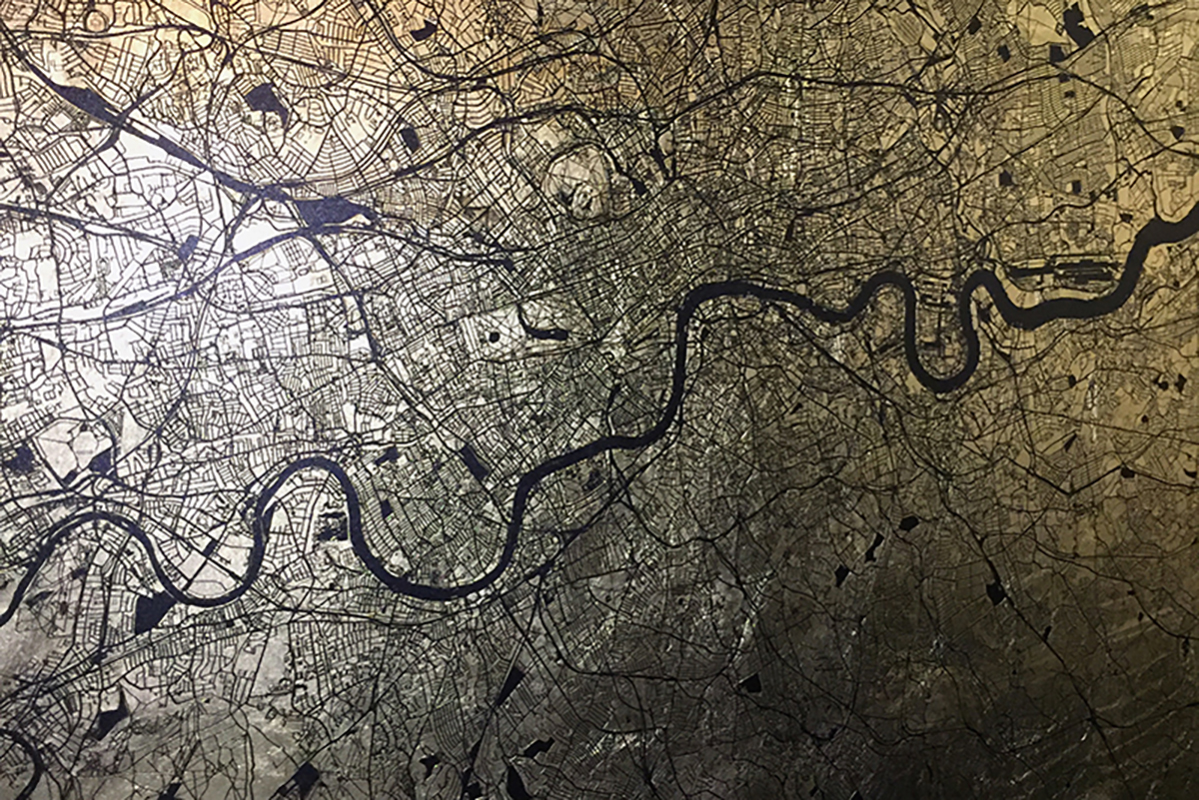

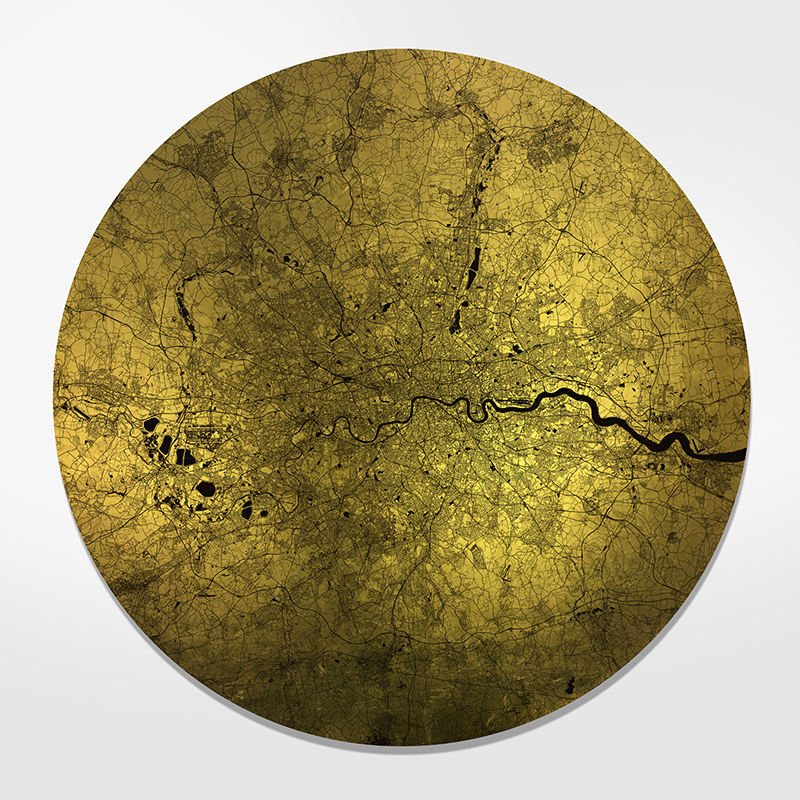

From London and New York to Hong Kong and the Honalulu, Ewan David Eason’s Mappa Mundi collection at the opulent 45 Park Lane hotel is much more than a gold-tinted view of this artist’s favourite cities. The luxurious pieces feature intricate lines of UV treated ink on gorgeous Dutch gold leaf to create maps that are both abstract and instantly recognisable.

With Eason’s pieces displayed almost casually around the lobby and bar of the five-star London hotel until 26 November, their appeal is obvious. Inspired by the medieval maps of the same name, Eason aims to create a snapshot of our ever-changing landscape – including fast-evolving cities like Dubai and Basra – using precious metals including 24-carat gold leaf and palladium leaf.

Inspired by artists such Paul Cézanne, Eason’s work has become increasingly popular, from exhibitions at the Barbican, Christies and the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, and he was also commissioned for a luxury property development in Kensington. Here, Eason exclusively tells Tempus about his inspirations, exhibitions, and how 3D technology is revolutionising the art world…

Ewan, how did your 45 Park Lane exhibition come about?

It was serendipitous. I know Patrick Hughes, who’s exhibited here previously, but it was purely coincidental. I was delighted to be approached, and started working on this exhibition about 18 months ago. 45 Park Lane is such a brilliant location, and opening during Frieze Week was fantastic.

How does seeing your work in situ here compare to being in a gallery?

I think both kinds of exhibition has its place. It’s great to see your art in a gallery, to display on a white wall and light the piece really well from the perfect angle – that’s brilliant. But I love exhibiting in living spaces, firstly because people can see how it might look on their own space, and secondly it gives you maximum exposure from people from all walks of life. 45 Park Lane welcomes guests on holiday, on business trips, people coming in for meetings or for dinner or cocktails with friends and family, so there’s something about the range of people who come into contact with the work that’s quite exciting. I’ve been doing this for six years and I’m still getting kicks out of every new piece that I do and I guess that’s wat I hope the viewer will get from these pieces. I hope people will see a journey, as well, and have a relationship with the works.

What is the inspiration for your Mappa Mundi collection?

Partly it’s the original Mappa Mundi from the 13th century. These were centred on significant holy places – like Jerusalem – or commissioned by landed gentry to highlight the importance of their land. For these works, the idea was to create these abstract egalitarian cities. The idea is that we are all precious and sacred. I centred each map on something that looked interesting to me, or something that was personal if I felt there was a story to tell. Sometime it was as simple as using the Fibonacci sequence as a reference point, but the Londonium map is centred on the Oxo Tower, where I proposed to my now wife, and Greater London is centred on the Royal Academy.

They look beautiful. What is the process of making each Mappa Mundi?

First I guild the whole surface – whether paper or aluminium – with luxurious gold leaf over three hours. The process of making the maps is a long process of combining references from Google maps, Open Street Maps and others, pulling all the information together and removing information like street names and landmarks in order to create that abstract image.

Why did you decide to focus on maps?

I think maps provoke an emotional reaction, they represent who we are when we have a connection to them. When you’re creating art, it is a conversation with you as the creator and the person looking at it – there’s a continuing dialogue. I do believe that art is alive, because it’s about the people. I’ve tried to reflect that in all my Mappa Mundi pieces by marking the city’s graveyards in black or aluminium, so everything that’s living is gold. I’m also like simple colour contrasts and abstract works, so for instance when you look at Hong Kong map, and that big water mass next to the streets – by distilling the colour options down you created a compliment and contrast. It makes the city itself seem less overwhelming.

What are you working on next?

My work is about opposites, so where the Mappa Mundi collection was about looking down on these cities, I’m now hoping to look up. I want to create the topography of a city or country, taking the mountains and converting them to white – so they look like clouds. It will be very ethereal. I’m looking to edge-light the pieces so you’re looking into clouds, and digitally printing them with UV treated ink. It’s very exciting.

How has digital printing and other technological advancements changed your work? Is there pushback in the artistic community about using this kind of technology?

You’re always going to get the purists who want you to paint landscapes, but I’d say I’m a conceptual artist, and I think the best way for me to create my idea is through what’s current. You utilise what you like and enjoy in whatever you do, and I like using technology and new advancements in my art. I’m also looking into 3D printing, and what I can do with that. I’d guess it’s like when paintbrushes were first eventing – or for instance, when Cézanne and the impressionists weren’t accepted in the salon, but now we see them as the masters. You have to take the criticisms and concerns with a pinch of salt. I think I have integrity, conviction and a message in my work, and so it’s up to time to tell.