This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Fake News: Artist Phillip Toledano asks if AI-generated photography is a threat or an artform

By Josh Sims | 17 January 2025 | Arts, Culture

Can AI generated photography be called an artform? Artist Phillip Toledano says it’s time to challenge our relationship with visual “facts” altogether

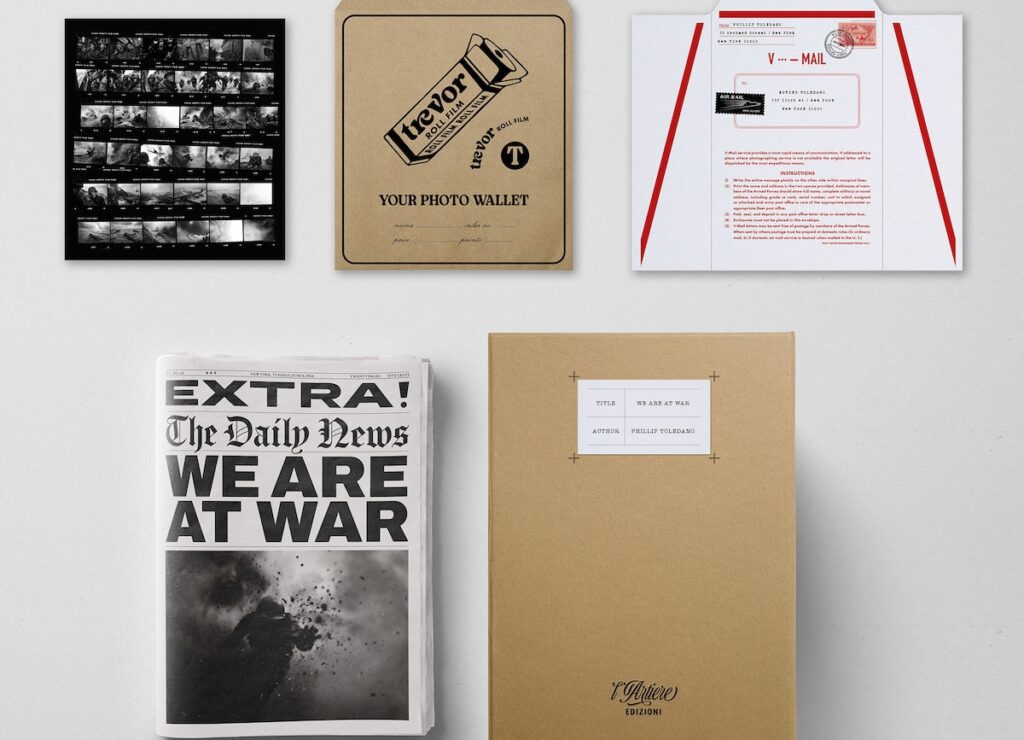

Phillip Toledano says he hopes visitors to his latest exhibition, We Are at War, will leave it feeling just a little bit annoyed. The New York-based British artist is showing a series of previously unseen photos by Robert Capa — the Second World War correspondent and only photojournalist present at the D-Day landings — at the Deauville Photography Festival in Normandy, until 5 January 2025.

Phillip Toledano says he hopes visitors to his latest exhibition, We Are at War, will leave it feeling just a little bit annoyed. The New York-based British artist is showing a series of previously unseen photos by Robert Capa — the Second World War correspondent and only photojournalist present at the D-Day landings — at the Deauville Photography Festival in Normandy, until 5 January 2025.

Famously, most of Robert’s shots were accidentally ruined in the lab when back in the UK. But now, artist Phillip has restored them — or so it would seem. As is revealed at the end of the exhibition, all of the hyper-realistic images were actually generated by the artist using Al.

“We’re at this historical, cultural hinge point where our relationship with images is being changed fundamentally, so it’s important people understand just how convincingly they can be lied to using Al,” says Phillip. “I hope that in picking an event in history that people are familiar with, that they know to be important, and a person who’s involved with that event — in this case an almost Biblical figure in photography — that it will make enough noise that people pay attention. If you can reinvent the past so persuasively, just imagine what you can do with the present.” Of course, says Phillip, photographs have been manipulated since the medium was invented: even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, was taken in by the Cottingley Fairies scandals — a series of photographs by young cousins Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, that purported to show fairies at the bottom of their garden in 1917. More recently, digital editing software has allowed many a Hollywood star to appear airbrushed and blemish-free via the magic of Photoshop.

Of course, says Phillip, photographs have been manipulated since the medium was invented: even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, was taken in by the Cottingley Fairies scandals — a series of photographs by young cousins Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, that purported to show fairies at the bottom of their garden in 1917. More recently, digital editing software has allowed many a Hollywood star to appear airbrushed and blemish-free via the magic of Photoshop.

But these are slow and complex methods that require resources and expertise. What Phillip underscores is that modern Al allows ‘fake’ images to be made with relative ease and at breakneck speed. What’s more, we now have the technology — social media — to disseminate those images globally before there’s time to assess their validity.

“[Photography] used to be the central arbiter of image as truth,” says Phillip. “Now there’s a technology that destroys that idea entirely. We all knew that paintings were entirely interpretive while photography, we believed, just told you what it saw. Not any more. Now, we are going to live in the perpetual state of feeling like we’ve just been had.” Aside from those images that are obviously surreal — such as Philip’s Another America exhibition at Planches Contact earlier this year — we’re already struggling to tell the difference between ‘real’ and Al-generated images. A University of Warwick study suggests that just 65% of people are able to identify whether an image is Al generated. What’s even more concerning is that participants typically found images of Al-generated people more attractive and trustworthy than those of real people.

Aside from those images that are obviously surreal — such as Philip’s Another America exhibition at Planches Contact earlier this year — we’re already struggling to tell the difference between ‘real’ and Al-generated images. A University of Warwick study suggests that just 65% of people are able to identify whether an image is Al generated. What’s even more concerning is that participants typically found images of Al-generated people more attractive and trustworthy than those of real people.

Other research has shown how easy it is to use fake images to convince people that they have a genuine memory of something that never happened to them.

Concerningly, a study found that most respondents believed an Al image of Pope Francis wearing a Balenciaga puffa-coat (an image that went viral late last year) was genuine, while an already-iconic photograph of the July 2024 assassination attempt on Donald Trump in Pennsylvania was, initially, widely denounced as fake.

Certainly, Al imagery is set to change our self-image too — mobile photo editing apps allow users to doctor photographs so that the resulting images bear little resemblance to any real event. More problematic, Phillip and others argue, is the impact Al image generation will have on those functions of society that help hold a democracy together — the judiciary, the media and politics. Major news organisations now regularly have to offer apologies and corrections for Al-edited images they’ve published. “People don’t vet much of what they see. When you know that people don’t have the time or ability or motivation to check, that makes Al-generated images an increasingly powerful weapon, especially when already most people can’t tell if an image is real or fake, and even more so when even a bad fake looks passable when viewed through a tiny cellphone screen, as many of us do,” says USA Forensic CEO Bryan Neumeister.

“People don’t vet much of what they see. When you know that people don’t have the time or ability or motivation to check, that makes Al-generated images an increasingly powerful weapon, especially when already most people can’t tell if an image is real or fake, and even more so when even a bad fake looks passable when viewed through a tiny cellphone screen, as many of us do,” says USA Forensic CEO Bryan Neumeister.

USA Forensic is a state-of-the-art independent digital forensics company, called on to assess the validity of images presented by lawyers as evidence in high profile court cases — such as the 2022 court case between actors Johnny Depp and Amber Heard — and working with governments to assess whether or not photos of hostages are genuine or not. “Al still has weaknesses when it comes to image-making. But I’ve seen [more and more] remarkable fakes over recent years,” he says.

Can anything be done to tackle this tidal wave of fakery? Earlier this year the EU passed the first ever Al regulations, forcing Al companies to label fake images. But that only scratches the surface. Some have argued that Al systems need to be limited so that they can’t produce fake Al images of news events, or that fake images need to come with a kind of indelible electronic watermark. But, as Bryan points out, any technological attempts to rein in Al image generation will be met with technological attempts to circumvent them. Maybe, as Phillip has it, breaking away from our dependence on photography as an expression of fact is inevitable – and perhaps no bad thing. If photography ever was trustworthy, now we have to learn not to trust.

Maybe, as Phillip has it, breaking away from our dependence on photography as an expression of fact is inevitable – and perhaps no bad thing. If photography ever was trustworthy, now we have to learn not to trust.

“We’ve only had photography as truth for the blink of an eye on the scale of human history, so I think we’re now just going back to how it’s been for the rest of time,” he says. “Photography [as an accurate record of events] was always an anomaly. Now we’re returning to the default setting – which is not having any clue.”

Besides, do we even care? Sometimes it seems not. It was the 20th-century Czech philosopher Vilem Flusser who first argued modern society is so saturated with images that we no longer attempt to decode them as being representations of reality; rather, we see reality as though through a series of images. Being captured in an image is what makes something real — that’s why some of us now see a destination’s “Instagrammability” as its primary value, why so many people watch live events literally through their phones.

“But we do have to think about these things more, insists Phillip. “Going forward, we can’t be in a position where we’re constantly having to ask, well, is that the President in that picture or not really? Who knows? How can we tell?”