This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Art and ecology collide at the Venice Biennale

By Claire McQue | 30 August 2019 | Culture, Travel

The contemporary art world’s most prestigious event, the 58th Venice Biennale, puts a spotlight on the art of change

In the Palazzo Ca’Tron, an elegant 16th-century structure on Venice’s Canal Grande, a shoal of blue marlin dance through a turquoise lagoon. Vines spiral around giant trees and, hanging from their branches, clouds of titanic insects slowly beat jewel-toned wings. There is all manner of clicks and hums, and the dense mass of plants seems to respond to my movements.

A Dionysian paradise, video and VR installation RE-ANIMATED (2018-2019) is created by artist Jakob Kudsk Steensen. While it feels like you have arrived in the world of James Cameron’s Avatar, Steensen in fact collaborated with field biologists and NGO workers to simulate real-world landscapes through 3D scanners and satellite terrain data. Science and natural history meet with his own vision; a hybridised world in which man-made technology and nature coexist; a complementary relationship, rather than a traditionally hierarchical one.

Steensen’s accompanying film is a digital recreation of Kaua’i, an island in Hawaii, created using 3D scanned flora. On the voiceover, ornithologist Douglas H Pratt speaks of his experiences the extinct Kaua’i ʻōʻō bird, endemic to the island. Pratt was the first ornithologist to explore Hawaii’s Alaka’i plateau and one of the last to hear the mating call of the Kaua’i ʻōʻō. A recording made in 1975 of this distinctive bird tragically seeking a mate that no longer existed got half a million views on YouTube in 2009. The creature finally became extinct in 1987 – the same year that Steensen was born.

Steensen is one of several artists addressing the climate crisis at the 58th Venice Biennale. The ecological conversation has been picked up by a host of contemporary artists who aim to use their cultural influence to address environmental issues.

At the Biennale, attended by more than 600,000 guests, artists are uniquely positioned to create a positive impact. In pavilions dotted around the floating city, art and activism collide independent of the purely political world that can be off-putting to so many, embroiled as it is in apocalyptic language and uncertainty. It can be difficult to personally relate to climate change, particularly in the West where the negative effects of climate fluctuations are less visible. Through their visual poetry, artists can break down the overwhelming reality of this clear environmental urgency into digestible, understandable molecules.

As the Venice Biennale opened in May, a report listing the one million species at risk of extinction due to human influence on the natural world was released, making Steensen’s recreation of the birds’ environment even more important. By including the Kaua’i ʻōʻō’s haunting mating call, Steensen acknowledges loss, but he also succeeds in positively retelling the story. >>

Visually and aurally, his film is beautiful. By reframing the factors that have shaped Kaua’i’s natural history with a futuristic setting, Steensen is on one hand digitally preserving and, on the other, indicating that an ecological reality defined by harmony between people and the natural world, is possible. You fall instantly under the spell of Steensen’s wild landscapes which the viewer, in control, has time to take in. Again, this is where his art comes up trumps.

Elsewhere at the Biennale, Ghanaian-born British filmmaker John Akomfrah also delves into landscapes of the past, in his searing three-channel video, Four Nocturnes (2019). He explores the link between historical attitudes to the environment and their damning impact on present-day Ghana. The colonial era is depicted in HD; rifles are fired and rulers’ game-hunts end in blood-streaked leopards strung between poles on villagers’ shoulders. It is painful to watch.

Akomfrah cuts to the present: sad-looking elephants chained for forestry work while a chainsaw is used to aggressively fell centuries-old wood. In the 62 years since Ghanian independence, it seems that little has changed as far as the hierarchy between man and the environment is concerned. By juxtaposing the harshness of the seasons – mighty sandstorms in the desert, soaring temperatures that kill an elephant calf, scorching lightning and finally, a deluge of rain – Akomfrah presents Ghana’s vulnerability to climate change. His vivid cinematography humanises his animal subjects. An underwater shot of an elephant family fording a churning river, a quirky frame of an elephant’s toenails… all make for a turbulent, emotionally charged watch. Akomfrah’s message is clear: destruction of the natural world is akin to destroying ourselves.

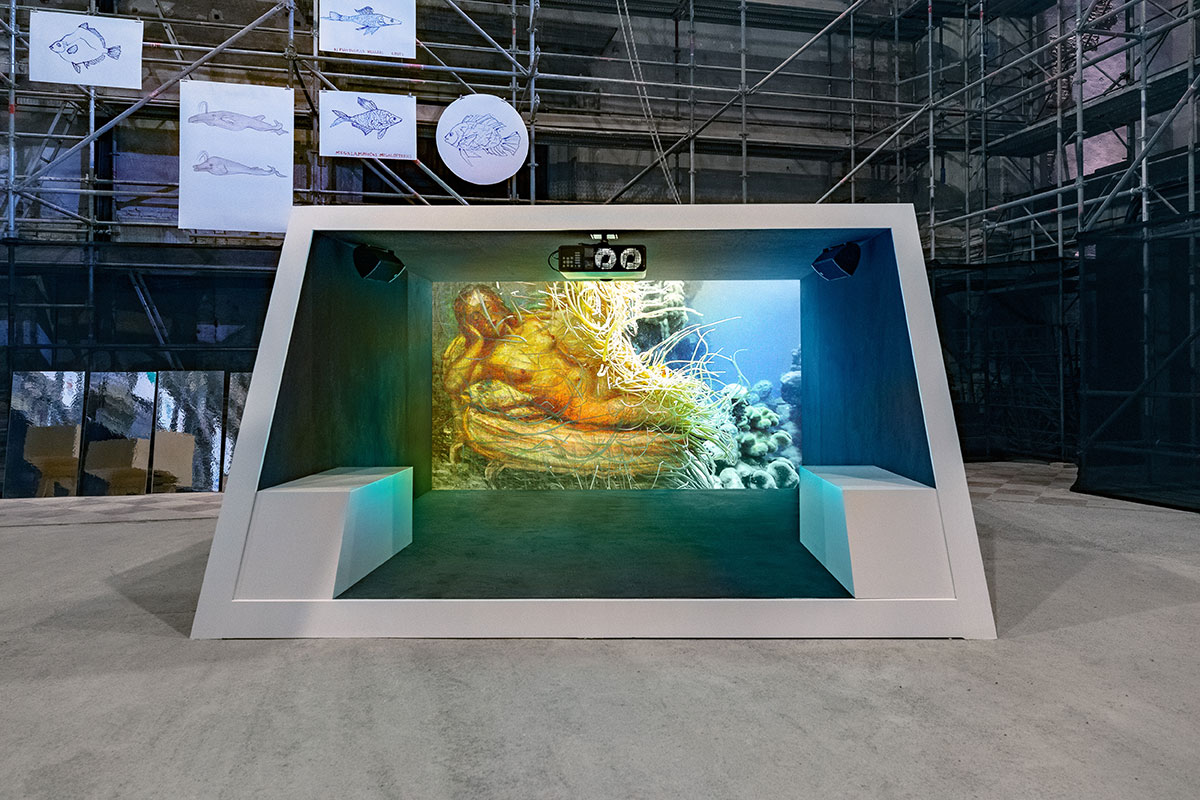

I travel from land to the sea with Ocean Space, a new centre for ocean advocacy and education housed in the ninth-century San Lorenzo church. Ocean Space’s inaugural exhibition, Moving Off the Land II, sees renowned US artist Joan Jonas explore the ancient land-based ancestors of today’s whales. A sperm whale’s disembodied clicks echo off the walls from a recording captured by marine biologist David Gruber, whose oceanographic research is woven into Jonas’s shimmering videos along with footage of the 83-year-old artist swimming in Jamaica. >>

Related: Art ex Machina: Meet the AI challenging everything we know about art and ethics

Jonas emphasises our undeniable, deep-rooted cultural connection to the oceans, infusing both science and fiction into her works, from author Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick to the poetry of TS Eliot and Emily Dickinson. She explores mermaid mythology (including the half-woman, half-fish Assyrian goddess Atargatis), the consciousness of an octopus and the dependence of all life forms upon light photons, as she explores the boundaries between people and ocean-dwellers. The presence of child- narrators in her videos speaks volumes. It’s the future generations both human and non-human, that our actions will affect, Jonas emphasises.

The permanent Biennale structures at the Giardini, with its pavilions ordered by nation rather than theme, shows a glimpse of how artists across the world are interpreting the global issue of this year’s theme –May you Live in Interesting Times. There’s more tsunami mythology and creation stories referenced in “cosmo-eggs” at the Japanese Pavilion, a recreated beach opera that laments the lethargic approach to climate action in the Lithuanian Pavilion, while Serbian artist Marina Abramovic’s “Rising” is a scary virtual reality experience in which the viewer is drowned by melting glaciers. In the Kiribati Pavilion, arresting films of islander customs presents a sad reality: the low-lying South Pacific island’s inhabitants could become the first climate refugees.

And what better place to tackle environmental issues than Venice, an ecosystem threatened by rising sea levels and unsustainable tourism? This year’s art is about a lot more than mere virtue-signalling. These contemporary artists are impressive, both in their employment of multiple disciplines and their decision to use their public platform to make environmental compassion and climate urgency a part of our culture.

See more exclusive features in the Tempus Design Edition, available now