This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Amanda Nevill reflects on her 17 years as CEO of the BFI and tells Tempus why cinema is Britain’s greatest export

By Michelle Johnson | 14 February 2020 | Culture

From pioneering streaming platforms to protecting historic film, Amanda Nevill celebrates British cinema

Cinema is changing. That’s the message from the British Film Institute, the charitable body whose mission is to champion and develop a sizeable domestic industry. 20-years ago, British film paled in comparison to the blockbusting Hollywood machine, but now it’s an impressive £8bn a year industry leading its field from production and infrastructure to crews and talent.

At the 2020 Golden Globes, top awards were scooped up by Brits: director Sir Sam Mendes for his war epic 1917; Rocketman’s Taron Egerton; Fleabag writer/actor Phoebe Waller Bridge; and Olivia Colman, who bagged Best Actress for The Crown just a year after her Oscars triumph with The Favourite. Add to this the boom in production capability, with many studios leaving the LA sunshine to make homes in London sound stages, where largely British crews deliver their expertise.

For Amanda Nevill CBE, who steps down as CEO of the BFI in February, this is the result of a fascinating cinematic journey; the slow building of an infrastructure that highlights the cultural, creative and economic talent of our film industry. Nevill began her career in national museums, working to establish photography as an artform with the Royal Photographic Society by hosting debut exhibits by the likes of David Bailey and Linda McCartney (“The UK was years behind the US,” she says), before moving to run the National Museum in Bradford, where she founded the Bradford Film Festival.

“I’ve always loved the arts, but never had the skills myself,” she tells Tempus. “When you’re passionate about something but have different abilities, you’re actually very well placed to facilitate space for others to create.” It’s this approach to creativity that has seen Nevill transform the BFI Southbank into a creative ecosystem for filmmakers, pioneer a streaming service that puts the history of British film at the fore, and actively invest in diverse talent to safeguard the industry’s creative and economic future – a move that has found backing from Star Wars and James Bond producers alike. Here, Nevill reflects on her greatest achievements, the impact of the BFI, and why British film is one of our most important exports.

Amanda, what were your impressions of the BFI when you joined?

I felt like the BFI was getting a really bad rap externally. It was in quite a financial mess, so my goal was to find two or three achievable things to impact that perception. They were quite terrific projects. First, we transformed the National Film Theatre into BFI Southbank, which is now a very cool destination showing exciting films, with great spaces to hang out and network. It’s changed how people interact with us completely. Richard Ayoade, who is a fabulous filmmaker, wrote his debut feature Submarine there. Secondly, we had to dramatically review how we preserve film, and began a two-year project with the University of Sheffield to protect and expand the National Archive. We house the most significant collection of film and television in the world – it’s truly extraordinary – and it all belongs to the public.

Why is the National Archive such a significant collection?

It is the most significant film and TV archive in the world, with some of the most complete and early historical footage in existence and our job is to acquire and preserve as much as we can. We made an incredible discovery when three milk churns, stuffed full of explosive nitrate film, were found in Burnley. It was made by Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon between 1898 to 1907. They would go to factories or football matches and film crowds, then erect an enormous projection tent and charge people a penny to watch themselves on moving film. It would have been phenomenal at the time, and today the historical significance is unmatched, as it’s the earliest moving footage of British people. This is part of our Britain on Film collection, which has over 10,000 titles and has had more than 60 million views on BFI Player. >>

Belle surprise: how Champagne has become this year's most surprising emerging destination

What was your approach in pioneering the BFI Player as a streaming platform?

I knew we had to get ahead of the curve with a streaming platform, and it’s been a rip-roaring success since launching in 2013. We spend so much energy ensuring Hollywood doesn’t dominate, so I wanted to make British and independent voices the heroes of the piece. We try to get that content on as many platforms as possible – we’re on Amazon Prime, Apple UK and Roku TV in the US – but I also love that notion of curating something very special for our community, just as we do with the BFI London Film Festival.

How important is the BFI London Film Festival as an international showcase?

The Festival is a unique moment in the arts calendar and its growth is a real testament to Britain’s standing. It positions the UK as a global leader, showcasing films from more than 70 countries with a David and Goliath approach: we present new work from small independent films and exciting new filmmaking voices, to the biggest awards contenders. For example, director Martin Scorsese chose to host the world premiere of The Irishman at the 2019 London Film Festival’s Closing gala. It’s a fantastic privilege.

Would you say we’re experience a boom in terms of exporting British talent?

You can absolutely say that, and it’s being sustained year-on-year. Look at the Golden Globe winners: Sam Mendes, Olivia Colman, Phoebe Waller Bridge, Taron Edgerton. 20 years ago, foreign studios would parachute in, make their films and leave, but now studios are making their homes here. Pinewood is expanding for Netflix; Sky is developing Elstree studios; Warner Bros. is investing into Leavesden. We have tax incentives of course, but that wouldn’t work without the very clever infrastructure of talent, crews and studios that we’ve created. Then, of course, the magic dust is that we’re the land of Shakespeare, Dickens, Brontë. We have fantastic theatres, museums, art galleries. It’s a very easy sell.

How important is cinema as a British export?

Film and television is worth £8bn to the UK economy and, year-on-year, our screen industries are the UK’s fastest growing sector. In the last financial quarter it was singled out as an industry that’s helping the country stay out of recession. Currently, about 40% of our film exports go to the EU, so there are careful negotiations happening to make sure that consumption isn’t damaged by Brexit. The BFI works shoulder-to-shoulder with the government to understand this economic impact and, since we merged with the UK Film Council in 2011, is able to act as R&D for the industry. We’re able to invest into debut filmmakers and help the industry discover and develop diverse new talent. As Orson Welles said: “A writer needs a pen, an artist needs a brush, but a filmmaker needs an army.”

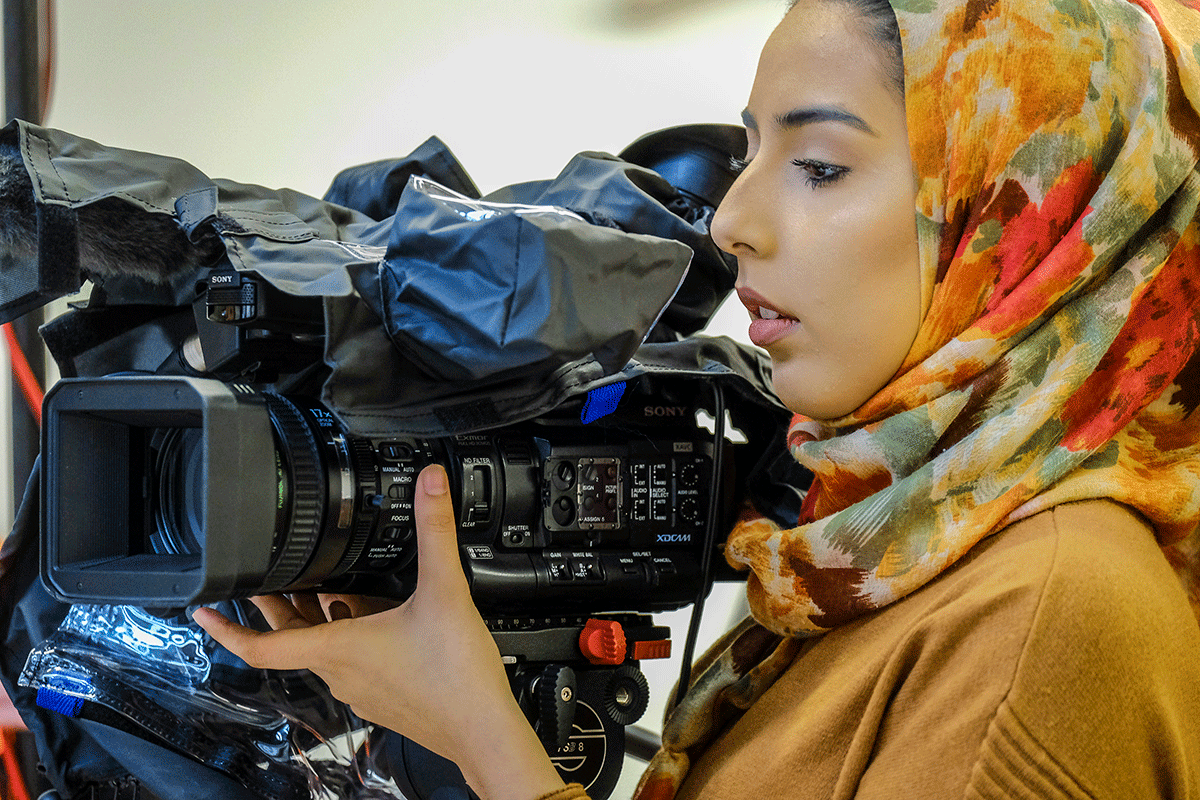

You mention diversity, which is a crucial talking point this awards season. How do you actively increased diversity in film?

Inclusion and diversity aren’t just nice things to have in the industry – they are absolute economic and creative necessities. If you take gender as an example: it’s insane to think you could live in a world and only have half a population’s stories. Creative people want to congregate in an environment that’s demonstrably culturally and socially diverse. The BFI has deliberately gone out to address inequality in all of its programmes. I launched the BFI Film Academy, which I’m completely passionate about, because if we want to have the greatest film industry in the world, then we need to find the best filmmakers and crews. We host 54 local workshops across the UK, open to people between the ages of 16-19. The best of those join an intensive residential course at the NFTS and the graduation ceremony is attended by industry professionals. It’s a deliberately diverse course – we welcome men and women, BAME candidates, LGTBQ+ candidates, people from different social and economic backgrounds – and we track attendees into their future career. This feeds into the BFI Future Skills Trainee programme driven by producer Kathleen Kennedy, who wanted to diversify recruits in the Star Wars franchise. Around 27 Film Academy students became paid trainees across a variety of craft and technical roles, and 96% of those were working on another film within three months. Barbara Broccoli has adopted the programme for the Bond films, and other studios are joining as well. >>

Why 120 millionaires are calling for international tax reform since the World Economic Forum

How important is fundraising to the BFI?

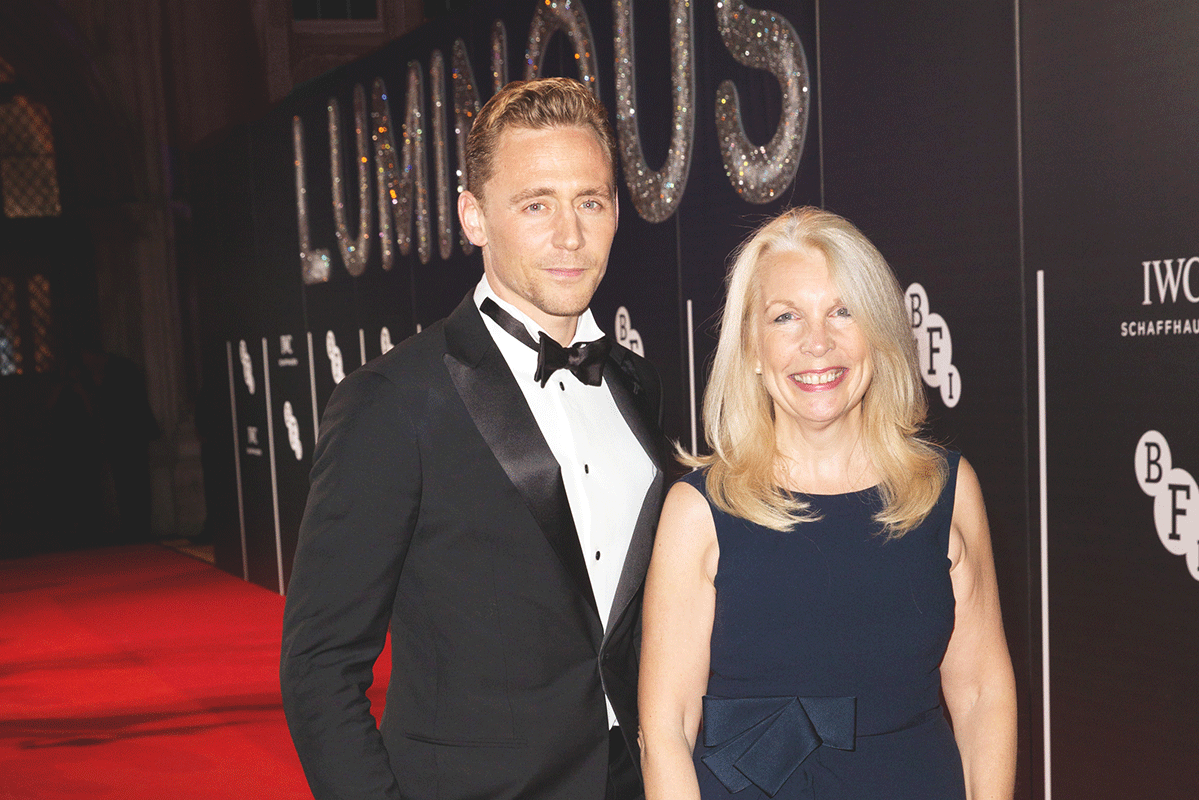

When I started at the BFI we had absolutely no fundraising capability. I brought Francesca Vinti over from the V&A Museum to become our executive director of fundraising and in the last 17 years we’ve built up this solid, fabulous body of patrons who really nourish the BFI. The Reubens got behind our educational activism, and our hugely popular Reuben Library at BFI Southbank, [Dunkirk director] Christopher Nolan CBE donates handsomely to support the National Archive – as does Martin Scorsese, who is a passionate champion of film restoration, which is a huge part of the work we do. Then we have the bi-annual Luminous Gala, which brings together industry, patrons and guests. At the last four galas, we’ve had Taron Egerton singing, Tilda Swinton speaking about film, Tom Hiddleston and Steve Coogan. Cate Blanchett and Olivia Colman are incredibly involved. We’re also very privileged to have National Lottery funding. I really want the industry to own the BFI and be proud of it, but we’ve never been complacent.

How do your patrons impact the BFI?

One of the things that has been so valuable is the insight our patrons provide. It’s like having direct contact with the people we deliver to, so it’s very nourishing. When things are a bit tough, a good supper with our patrons can make us bounce back very easily. But it’s important for any philanthropist to know their commitment is worthwhile. The BFI is able to show direct, tangible results from our fundraising efforts, whether that’s the opening of the BFI Reuben Library or the restoration of the Hitchcock Nine. We were able to bring Hitchcock’s early silent films back to life as a direct result of fundraising, and they toured around the world as part of the 2012 Cultural Olympiad. One of my great memories is opening the Shanghai Film Museum in 2013 with a premiere of Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1929), newly scored by a Chinese composer. The event was instrumental in getting a co-production treaty signed between China and the UK.

What’s the most important thing you’ve learnt as a leader during your time at the BFI?

To make things happen. BFI’s former chairman Greg Dyke helped me realise that certain quirks of my personality were actually leadership traits I needed to be a better CEO. I always have a million ideas; when I came into the office after a holiday people would almost be hiding in cupboards knowing that I’d have 50 things I wanted to start right now. But Greg assured me that people are looking to the CEO to take the lead. There are always reasons to delay but, as a CEO, you have to learn when to use your privilege and say: this is the time to take action. I’m so happy to be stepping down while momentum is so high and couldn’t be happier to hand the reins to Ben [Roberts, CEO]; we’ve worked together for eight years and he’s going to be fantastic in the role. I imagine he might find himself taking some leaps in the dark but, as I’ve learnt, people will look back and see that as an important part of leading an innovative organisation.

Read more from Britain's most influential leaders in issue 66 of Tempus Magazine, available now