This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

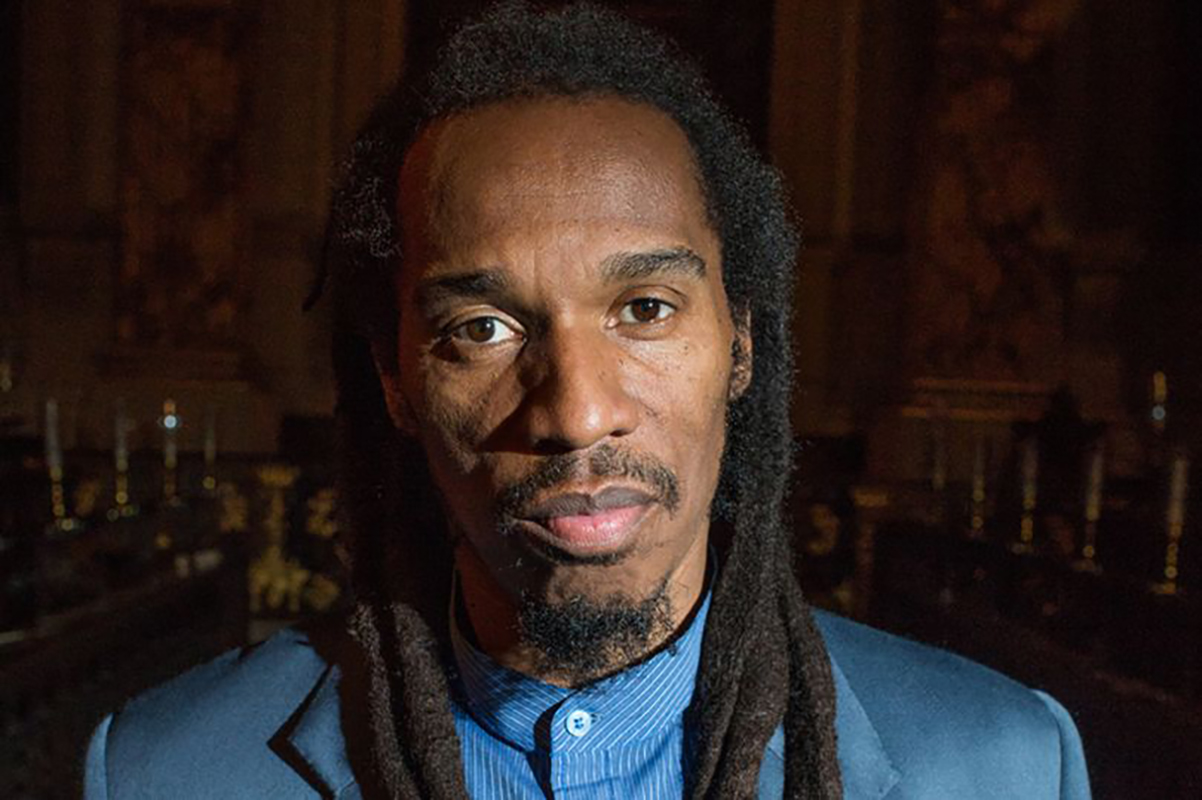

Benjamin Zephaniah reflects on his Life and Rhymes tour and why female poets are leading the way in performance

By Michelle Johnson | 20 June 2018 | Culture

The Peaky Blinder’s actor has shared his accomplishments – and his demons – in his autobiographical UK tour

British performance poet Benjamin Zephaniah does not shy away from his demons. Whether taking on gritty roles in the latest series of super stylish Peaky Blinders or talking candidly about his tumultuous family history, the critically acclaimed dub and reggae poet – ranked by The Times as one of Britain's top 50 post-war poets – has been airing his political and personal experiences in his UK Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah Tour.

Launched alongside his autobiography of the same title, the grand finale of the nationwide tour will take place at the prestigious Ledbury Festival on 30 June, with a second tour already in the works for 2019. It is Zephaniah's passion project, he tells Tempus, during which he has been taking the opportunity to champion female poets and speak out against the toxic behaviour and violence that plagued his younger years.

The poet, who teaches performance poetry at Brunel University London, said it was his political activism in the 1980s that educated him against violence, and taught him to use his popularity to champion young talent. Here, he speaks to Tempus about his tour, his teaching methods, and the business of poetry.

Benjamin, what keeps bringing you back to live performances?

When you're on stage live anything can happen, so you have to be able to change an adapt depending on what's going on in the world or the audience you're talking to. I also have dyslexia, and have never been good at writing things down, so I compensate in different ways. I tend not to think about a show too much in advance, so there was no real plan when I began the tour – I just try to be natural and honest. That approach actually helps me with public speaking, I think, and I present all my lectures in that way as well.

The Life and Rhymes tour is based on your autobiography, which really takes people behind the scenes of your most famous poems. What was it like to write?

A lot of writing this book was either from memory or from talking to others. In a way, I almost had to research myself. I spent hours talking to my mother, because I wanted to include elements of her life as well – how she came to England from Jamaica and how her experiences compared to her sister, who stayed in Jamaica, and my cousins who are still over there. And then there was the political landscape, and everything going on around me in the 1980s and 1990s. One of the things you'll notice in the book is that it's not just about me but the politics of the time. >>

Related: The Alienist's Luke Evans on costumes, characters and taking on Hollywood

You often speak about your challenges and politics in your poetry, but what have been some of the defining moments in your career?

It's a bit weird, reflecting this way about the life that I'm still living. It's only when people like yourself comment on some of the things I've done, or the people I've met, that it really sinks in. For me, the good and the bad is all a part of me, but there are big influences as well. I'm so glad I was alive in the time of Nelson Mandela and that I got to meet him. I was able to work with Bob Marley and became friends with Maya Angelou – two of my heroes. But I'm also influenced by people I've never met, like Stephen Hawking, who had a real impact on our lives. I think about when the history of the world is written, and the fact that my name's going to be in there around the same time as these people. It's been a fascinating journey.

Do you have any concerns about the future of poetry as an artform?

No. Essentially performance poetry is all part of the oral tradition, and in that sense it's been around as people have been talking to one another. I'm convinced that poetry was the first art form, around long before we started painting and writing, and it didn't become an academic exercise until the invention of the printing press. I've learned that a lot of contemporary criticism about performance poetry is either based on the idea that William Shakespeare is the only true poet, or based on attacking women for getting up and speaking about their experiences. But in fact, many of the best poets around right now are women. It's their time, and the work of women that I admire really helps to teach me about myself as well.

You are a professor of poetry at Brunel University. How do you approach lectures?

I think my lectures are definitely informed by my gigs. When I first started teaching at Brunel, other students would miss their lectures in order to come to mine. Performance poetry is a fantastic way to build confidence or public speaking skills, or to face your fears, so I try to keep everything fresh and interesting. Once I was teaching ways to memorise poetry for performances and how to use your body to help you perform, so to do that I was doing press ups while reciting a really difficult poem. By the time I went back to my office a student had tweeted it and someone in Jamaica had already responded. That taught me to try to make my lectures like an event – with a bit of improvisation thrown in, of course.